Introduction

This article embarks on a journey of exploration, delving into the intricate realms of philosophy by revisiting the concept of Husserlian Transcendental Phenomenology. However, what sets this endeavor apart is its unique perspective, as it scrutinizes the principles of Transcendental Phenomenology through the lens of Vedanta, particularly the Mandukya Upanishad. The Mandukya Upanishad, a profound text in the Advaita Vedanta tradition, becomes a guiding beacon for understanding consciousness and reality. Through a comparative analysis, this paper seeks to draw parallels between these two philosophical frameworks, which originated at different times and places.

In the following pages, we will first shed light on the core concepts of the two philosophies, especially how both converge on themes of consciousness exploration, unity of experience, and the consideration of a transcendent dimension despite their disparate origins. We will demonstrate this by offering diverse examples.

Revisiting Husserlian Transcendental Phenomenology

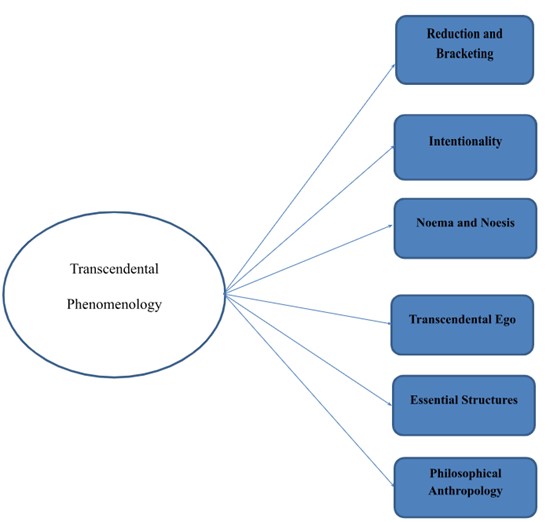

The Husserlian transcendental phenomenology is a philosophical method and framework developed by the German philosopher Edmund Husserl in the early 20th century. It is a foundational approach within the broader phenomenological movement, which seeks to describe and analyze the structures of human experience as they appear in consciousness. Transcendental phenomenology, in particular, focuses on the fundamental conditions of possibility for human experience (Zahavi, 2017). Key aspects of the Husserlian transcendental phenomenology are shown in Figure 1.

This phenomenology is a method that involves suspending assumptions about the external world to rigorously examine the structures of consciousness and experience. By focusing on intentionality, noema and noesis, the transcendental ego, and other essential structures, Husserl aims to uncover the universal features that characterize human experience (Ashworth, 1999). This method has had a profound influence on various fields, including philosophy, psychology, and the social sciences (Wertz, 2016).

In the following section, we will first discuss key aspects of Husserlian transcendental phenomenology.

Reduction and Bracketing:

Transcendental phenomenology employs a method called epoché, or bracketing. This involves setting aside or “bracketing” all assumptions and preconceived notions about the external world. The philosopher suspends judgment regarding the existence or non-existence of the external world to focus solely on the phenomena as they appear in consciousness (Dörfler & Stierand, 2021).

Intentionality:

Husserl emphasizes intentionality – the idea that consciousness is always directed towards something. All consciousness is consciousness of something. Whether perceiving an object, thinking about an idea, or feeling an emotion, consciousness is inherently relational, pointing beyond itself to objects in the world (Schacht, 1972).

Noema and Noesis:

The objective aspect or meaning of an intentional act is called the noema. It represents the intended object as it appears in consciousness. The subjective aspect, or the act of consciousness itself, is called the noesis. It is the experiential side of intentional acts – the lived experience of consciousness (Rassi & Shahabi, 2015).

Transcendental Ego:

The transcendental ego is the foundational subjectivity that makes all experience possible. It is not an empirical ego but rather the transcendental condition for the possibility of consciousness. The transcendental ego is the unifying and organizing principle that allows diverse experiences to form a coherent unity (Schmitt, 1959).

Essential Structures:

Transcendental phenomenology aims to identify and describe the essential structures of consciousness. These structures include intentionality, temporality, and the intersubjective nature of experience. By analyzing these structures, phenomenology seeks to uncover the universal and invariant aspects of human experience (Schacht, 1972).

Philosophical Anthropology:

Through transcendental phenomenology, Husserl also engages in a form of philosophical anthropology, exploring the nature of human subjectivity and the conditions that make experience and knowledge possible (Köchler, 1982).

Revisiting Mandukya Upanishad and drawing parallels with Husserlian transcendental phenomenology

In this section, we will first talk about the Mandukya Upanishad through different examples and then draw parallels between it and the Husserlian transcendental phenomenology.

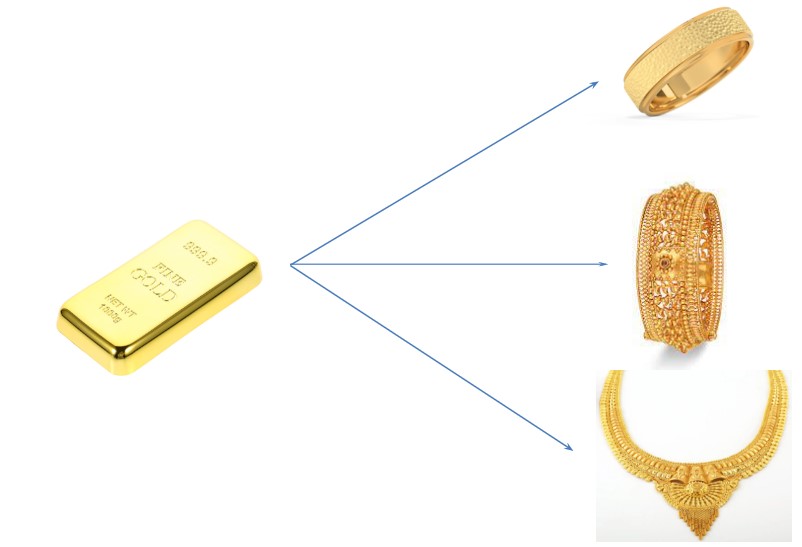

So, let us start with an example. Assume you own a gold ring, a gold bangle, and a gold necklace, all of which have the same weight. Your belief that all three are different stems from your lack of knowledge or ignorance. Gold embodies their fundamental nature, i.e., the gold is distinct in each of the three, yet it is present inside each of them. This example illustrates how the Mandukya Upanishad guides us in discovering the fundamental nature of reality. Here, it shares a similarity with the Husserlian transcendental phenomenology, as both emphasise the need for bracketing biases and ignorance in order to uncover the true essence. Figure 4 explains the same argument.

The Mandukya Upanishad is one of the shortest Upanishads and is considered one of the most important in the Advaita Vedanta tradition. It is a part of the Atharvaveda and consists of just 12 verses. Despite its brevity, it delves into profound metaphysical and philosophical concepts, particularly focusing on the nature of reality and consciousness. According to the upanishad, pure consciousness is not something that may be seen, felt, or talked about (Swami, 2014). It introduces four states of consciousness : –

- Waking State (Vaisvanara): The state of consciousness experienced in the waking world

- Dreaming State (Taijasa): The state of consciousness experienced in dreams

- Deep Sleep State (Prajna): The state of deep, dreamless sleep

- Turiya (the Fourth): The transcendent state beyond the three states mentioned above, which is the true essence. It is apart from all and reflects in all.

We can discern parallels between each key aspect of the transcendental phenomenology and that of the Mandukya Upanishad.

Reduction and Bracketing: Both involve a suspension or transcendence of ordinary reality. In Husserlian reduction, it is the bracketing of assumptions about the external world (Schmitt, 1959); in the Mandukya Upanishad, it is the realization of a state of consciousness beyond ordinary waking, dreaming, and deep sleep (Krishnananda, 1996). The goal in each case is to focus on the essence. Reduction in phenomenology allows us to examine the essence of consciousness and phenomena, while the Mandukya Upanishad guides practitioners toward understanding the essence of the self and ultimate reality.

Intentionality: Husserlian intentionality involves a form of transcendence where consciousness reaches beyond itself to engage with the world (Bernet, 1990). Similarly, Advaita Vedanta, as expounded in the Mandukya Upanishad, emphasizes the non-dual nature of ultimate reality (Brahman) (Durga et. al., 2018). The concept of intentionality, with its inherent directedness towards objects, finds a parallel in the Upanishadic emphasis on transcending the individual self to realize the non-dual nature of reality.

Noema and Noesis: The Husserlian distinction between noema (the ideal content or meaning) and noesis (the act of consciousness) (Zahavi, 2004) finds a parallel in the Upanishadic distinction between the eternal self (Atman) and the changing states of consciousness (waking, dreaming, and deep sleep) (Krishnananda, 1996). The Upanishad emphasizes realizing the unchanging reality beyond the transient states of mind.

Transcendental Ego: Both explore aspects of consciousness that transcend ordinary experiences. The Transcendental Ego and Turiya both signify a dimension beyond the changing states of consciousness. Also, both traditions emphasize a non-dual understanding of reality. In phenomenology, the Transcendental Ego is not an object but the source of all intentional acts (Morriston, 1976). Similarly, in the Mandukya Upanishad, the unity of Atman and Brahman implies a non-dualistic nature of reality (Veeraiah, 2015).

Limitations

Although there are several parallels between the Mandukya Upanishad and the Husserlian transcendental phenomenology, it is important to consider that these two concepts originate in two different places and time periods. While the Mandukya Upanishads do not present any concept of personal god, they explore the nature of reality, the self (Atman), and the ultimate reality (Brahman). They are foundational texts in Hindu philosophy that talk about the concept of “OM”. In contrast, the Husserlian transcendental phenomenology does not include a concept of religion within its methodological framework. It is primarily concerned with the analysis of consciousness and the structures of experience, leaving questions about God and metaphysics to other areas of philosophy or personal beliefs.

Furthermore, the Mandukya Upanishads are spiritual and religious texts that aim to guide individuals toward spiritual realization and liberation (moksha). They use symbolic language and metaphors to convey profound truths about the nature of the self and ultimate reality, whereas phenomenology is a philosophical method concerned with the rigorous examination of consciousness and experience. It is more methodological than spiritual, and its primary goal is to describe and analyze the structures of consciousness without making metaphysical commitments.

Conclusion

This article has undertaken a captivating journey into the realms of philosophy, reexamining the Husserlian Transcendental Phenomenology through the prism of the Mandukya Upanishad. Through our exploration, we have discovered striking parallels between these seemingly distinct philosophies. Despite originating from diverse cultural and temporal contexts, the shared themes of consciousness exploration, intentionality, and the quest for a transcendent dimension highlight the universal nature of human inquiry into the nature of reality.

In the grand tapestry of human thought, this exploration serves as a testament to the interconnectedness of diverse philosophical traditions. As we continue to unravel the mysteries of consciousness, the parallels discovered in this article invite scholars and thinkers to engage in a broader conversation that transcends cultural and temporal boundaries.

References

Ashworth, P. (1999). ” Bracketing” in phenomenology: Renouncing assumptions in hearing about student cheating. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education, 12(6), 707-721.

Bernet, R. (1990). Husserl and Heidegger on intentionality and being. Journal of the British Society for Phenomenology, 21(2), 136-152.

Dörfler, V., & Stierand, M. (2021). Bracketing: A phenomenological theory applied through transpersonal reflexivity. Journal of Organizational Change Management, 34(4), 778-793.

Durga, T. K., Sridhar, M. K., & Nagendra, H. R. (2018). Consciousness in upanishads. International Journal of Sanskrit Research, 4(5).

Köchler, H. (1982). The phenomenology of Karol Wojtyla: On the problem of the phenomenological foundation of anthropology. Philosophy and Phenomenological Research, 42(3), 326-334.

Krishnananda, S. (1996). The Māndūkya Upanishad. Rishikesh: Divine Life Society.

Morriston, W. (1976). Intentionality and the Phenomenological Method: A Critique of Husserl’s Transcendental Idealism. Journal of the British Society for Phenomenology, 7(1), 33-43.

Rassi, F., & Shahabi, Z. (2015). Husserl’s Phenomenology and two terms of Noema and Noesis. International Letters of Social and Humanistic Sciences, 53, 29-34.

Swami Sarvapriyananda at IITK – “who am I?” according to Mandukya Upanishad-Part 1. (2014). Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=eGKFTUuJppU

Swami Sarvapriyananda at IITK – “who am I?” according to Mandukya Upanishad-Part 2. (2014). Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=F0dugc4TrlE

Schacht, R. (1972). Husserlian and Heideggerian phenomenology. Philosophical Studies: An International Journal for Philosophy in the Analytic Tradition, 23(5), 293-314.

Schmitt, R. (1959). Husserl’s transcendental-phenomenological reduction. Philosophy and Phenomenological Research, 20(2), 238-245.

Veeraiah, C. (2015). The pursuit of happiness: An Advaita Vedanta perspective. Happiness and Hopei, At Lisbon, Portugal. Retrieved from https://www. researchgate. net/publication/305703294_The_pursuit_of_happiness_An_Advaita_Vedanta_perspective.

Wertz, F. J. (2016). Outline of the relationship among transcendental phenomenology, phenomenological psychology, and the sciences of persons. Schutzian Research, 8, 139-162.

Zahavi, D. (2004). Husserl’s noema and the internalism‐externalism debate. Inquiry, 47(1), 42-66.

Zahavi, D. (2017). Husserl’s legacy: Phenomenology, metaphysics, and transcendental philosophy. Oxford University Press.

Author: Rishav Raj

About the Author: Student of PhD03